From sermons to saunas: what’s the future for historical places of worship?

By Alexandra Revell, Project Manager

This September I was awarded a Masters in Quantity Surveying with Distinction at the University College of Estate Management. This MSc has been a great opportunity for me to gain a solid academic foundation to the work that I do for clients and will allow me to achieve RICS accreditation through the APC, which I hope to complete in spring 2018.

For my dissertation, I selected a topic that I have personal interest in and undertook independent research. I chose to look at the future of historical places of worship by reviewing options for their restoration or conversion. Religious buildings make up the third largest group on the Scottish Civic Trust’s Buildings at Risk Register, and the Church of England closes on average 24 churches a year (Church Care, no date). A new use is found for more than 50% of the closed churches; including an alternative community use (46%), vested in another body (27%) and commercial use (27%). The research was important to me because I believe that the issue of how to deal with places of worship is reaching a critical point. One of the main concerns for those currently responsible for the upkeep of a place of worship is who will look after their church when they are no longer able or around to do so; ‘as they look around at their ageing and diminishing number of colleagues they see neither how this process could continue when they are gone, nor any signs that a new process is being established to replace it’ (Living Stones, 2010). Furthermore, with the UK finding itself suffering from a major housing crisis, churches could be a small step towards providing more homes either through conversion or demolition.

‘The churches of England are the nation’s heritage; they thread through the history of the land, stretching almost two thousand years from Joseph of Arimathea’s wattle and daub church at Glastonbury.’

Child, M., Churches and Churchyards, (2007)

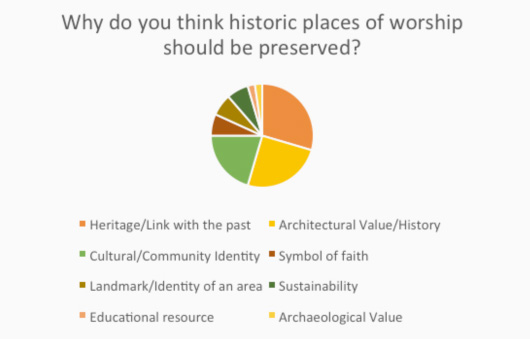

I initially sent a survey to clients, contractors and consultants to gauge the general consensus regarding the future of church buildings. One of the questions asked why historic places of worship should be preserved:

The results also showed that most participants feel that churches should remain open to the public and should benefit the community, rather than become private spaces such as homes that can only be appreciated by a few individuals.

‘Our churches are our history shown in wood and glass and iron and stone’

(Betjemen, 1996)

It was somewhat surprising then, with clearly many voices speaking out against the demolition of churches that one voice in support of the closures (and therefore potential loss) of churches is the Church itself including the Right Rev John Arnold, the bishop responsible for 22 planned church-closures in the north west. If these buildings are too burdensome for the church, some argue, then it is time for the church to sever ties with them rather than concerning itself with architecture and archaeology.

I then explored possible options for churches that would mean that they remained in public use, and also looked at a few examples of their conversion into private residential buildings.

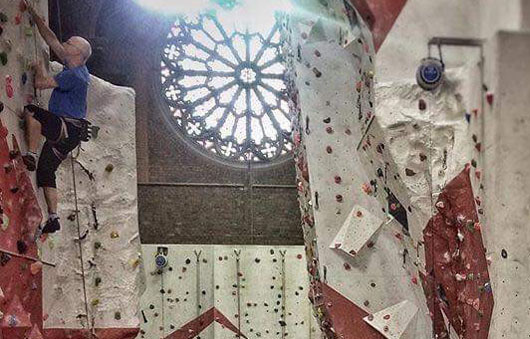

Image 1: Stairway to heaven: St Benedict’s church, Manchester, has been converted into a climbing centre.

Image 2: Restoration to restaurant: Oran Mor in Glasgow is now an arts and entertainment centre, formerly Kelvinside Parish Church.

The studies allowed me to research many extremely interesting and innovative examples of conversion, from the Manchester Climbing Centre (image 1) to entertainment venues such as Oran Mor in Glasgow (image 2) to luxury homes such as the £50m Knightsbridge Church renovated by luxury developers Rigby and Rigby featuring a gold leaf pool room, a juice bar, home cinema and sauna (image 3).

Image 3: From sermons to saunas (and cinema, juice bar and pool): this Knightsbridge church is now a luxurious private home.

This research gave me an appreciation for the huge potential that that church buildings have, so much so that it was not possible for me to conclude on the perfect recommendation for each building as there are so many variables. A one-size-fits-all solution is impossible. Instead, the future of these buildings should emerge from working with communities and responding to the church’s environment rather than a sweeping generalisation made at national level.

I hope I will be able to apply these studies by volunteering with Historic England to expand their Heritage at Risk Programme which aims to record all the Grade II listed (or higher) buildings across the country.

Thanks to Churchill Hui

My course was part-time and long-distance so that I could study whilst having a full-time job. This has obviously therefore been a busy couple of years but working has allowed me to apply my studies to real-world examples and that’s made it much more rewarding. As well as sponsoring my course, Churchill Hui has given me study leave throughout the last two years when I needed to revise or finish an essay, which has been useful and allowed me to keep on top of my studies without losing all of my free-time. The whole team has been very supportive and everyone has chipped in with essay ideas and moral support. Students on long-distances course can feel isolated so having supportive colleagues has been a great help.

Contact Alexandra via Linkedin

Images used with kind permission from Rigby and Rigby, Kris Kesiak Photography and Manchester Climbing Centre.